Today’s topic is more so about covering jargon used in music than actually understanding of music. However, the use of this terminology can help clear-up some confusion from previous lessons as well as aid in helping understand the next lessons.

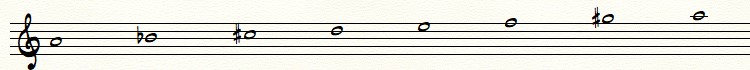

When we talked about the major and natural minor scales, we talked about how they are made up of 7 different pitch classes with a repeat at the octave. Previously, we have just been calling the pitches of the scale just by there ascending number.

So, for example: we call the second note of the scale the second degree.

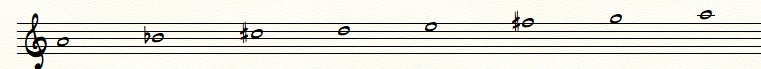

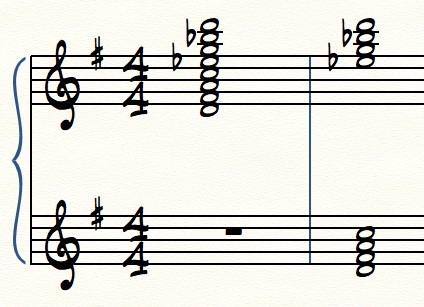

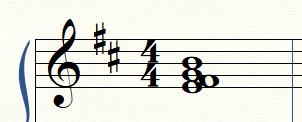

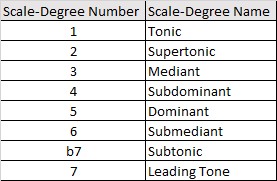

Well, there are some specific names for those pitches that make up the scales:

Now, going back to our previous example: when referring to the second scale degree of the major or natural minor scale, we would say the “supertonic” of the scale.

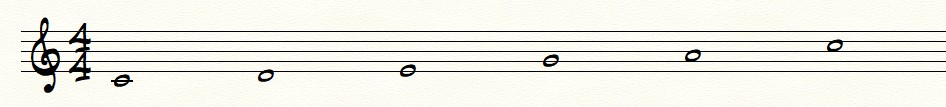

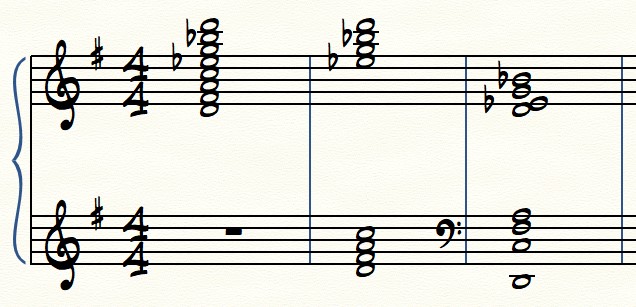

To further drill-in this terminology, let’s review the major pentatonic scale.

Remember that the major pentatonic scale has the same pitch class collections as the major scale… but 2 pitches less (hence how “penta” means “five”).

What scale degree names are in common with the major scale AND the major pentatonic scale?

Looking at the chart above, it would be:

- The tonic

- Supertonic

- Mediant

- Dominant

- and submediant

And there you! That’s how you name pitches by their scale-degree names.

Thank you so much for taking the time to read! Feel free to comment, share, and subscribe for more daily tips below! Till next time.