As mentioned previously, Renaissance era counterpoint was vocal – but that doesn’t mean that they song only on “ooo”s and “ahh”s. Their lyrics usually came from liturgical texts, like psalms.

Before beginning to write a contrapuntal piece, one must be able to master the style of writing a single melodic line before trying to weave multiple independent lines together. This blog will talk about the process of doing so.

First thing you want to do is decide on the text you want to set to music.

Second, you will need to decide on the appropriate mode. Each mode has its own qualities an shades to best fit the mode of the text.

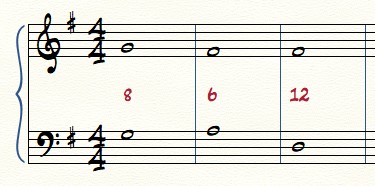

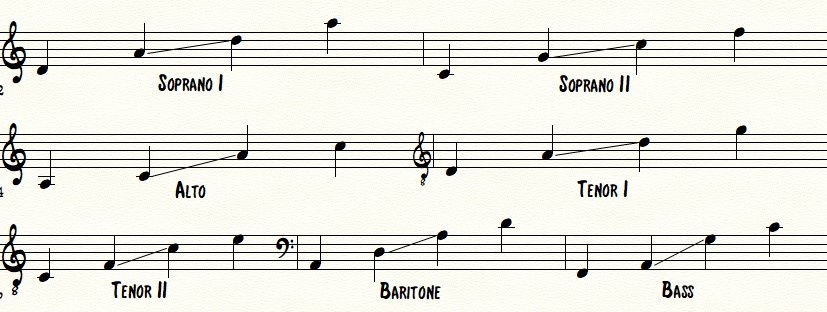

Third, you will want to assign the melody to the right voice. Look below at the different voice ranges. The out-most notes are the “extremes of the voice range, while the two pitches in the middle connected by a line suggest the comfort range:

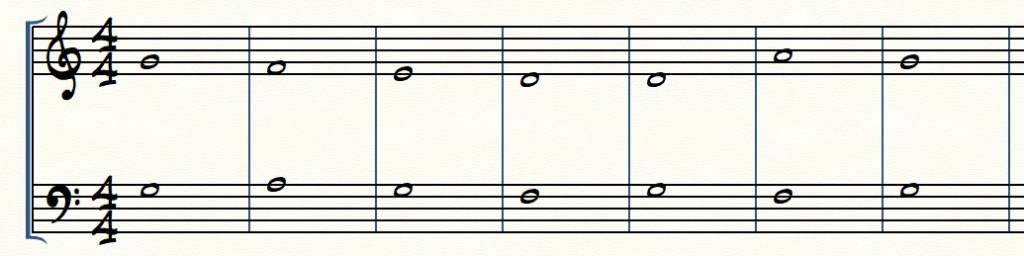

Fourth, start the melody on the authentic or plagal pitch. Adjacent voices (when we start incorporating more melodic lines) with start on the opposite choice.

Fifth, start writing your melody to shape the text. Keep in mind:

- Word Painting – doing something musical to invoke the images of the lyrics

- Accenting important words with skips and leaps

- Keeping the overall melodic line moving with stepwise motion instead of repeating notes

- Be sure to cover the range of the mode within the limits of the vocalist without hitting the extremes too much

- Have a interesting melodic contour

- Avoid outlining or moving by dissonant intervals

Sixth, cadence by stepwise motion from above or below.

- The Dorian, Mixolydian, and Aeolian modes should have the their leading tones raised.

- Ionian and Lydian already have natural leading tones and require no raising of pitches.

- Phrygian has its own unique cadence of going down by half-step and going up by whole-step.

- The Aeolian mode can have a “Phrygian cadence” by lowering the tone from above.

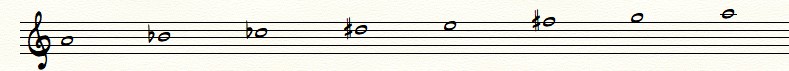

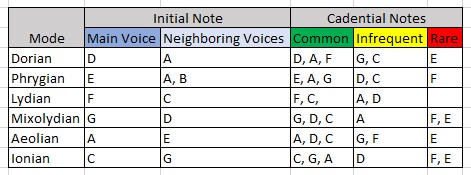

Below is a chart of the modes as if they were in the key of C:

Thank you so much for taking the time to read! Feel free to comment, share, and subscribe for more daily tips below! Till next time.