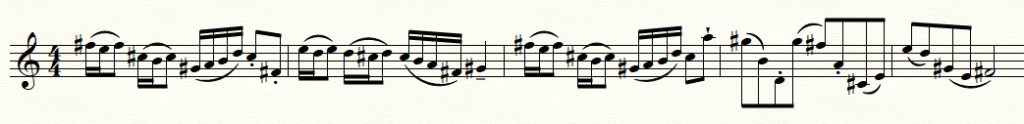

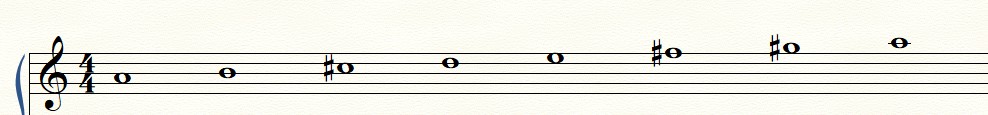

Read, analyze, play, and/or listen to this compositional segment below:

Now, write out all of the note letter-names that you see where used in this small composition.

You should get (in order of appearance): { A, C#, E, F#, D, B, G#}

What we have written above is the composition’s pitch-class collection, or a collection of all the pitches listed by their letter-names used.

Time to introduce a new concept. A scale, which is a pitch-class collection but organized in a ascending/descending manner in an alphabetized way.

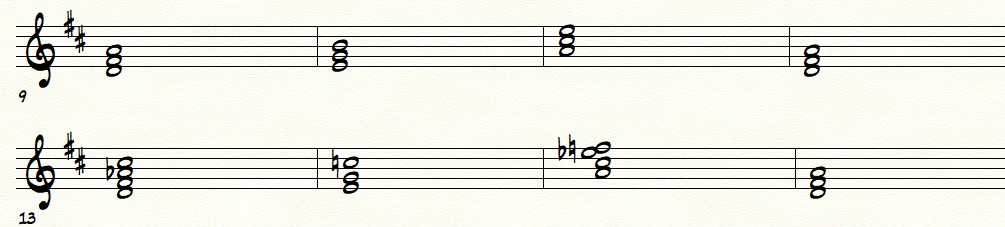

Which… using the same example above, if we put the pitch-class collection in an alphabetical order, it would be: {A, B, C#, D, E, F#, G#}

So, what kind of scale is this? Well, to spoil the answer – this is a major scale. But how can we tell? Just look at the intervallic distances between the notes.

A major scale is made up of a pattern of notes set apart from each other in an ascending manner of whole-step, whole-step, half-step, whole-step, whole-step, whole-step, half-step (which returns to the starting pitch). You can also think of this as M2-M2-m2-M2-M2-M2-m2.

So now, let’s take a look back at our pitch-class collection:

Does it match the pattern of the major scale interval formula? Yes it does!

Try now for an exercise by taking any starting pitch and see if you can build a major scale of your own!

Thank you so much for taking the time to read! Feel free to comment, share, and subscribe for more daily tips below! Till next time.