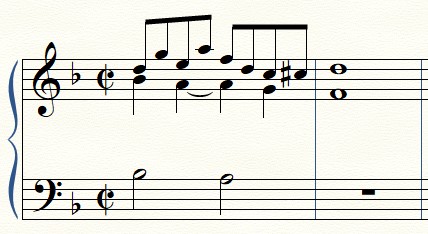

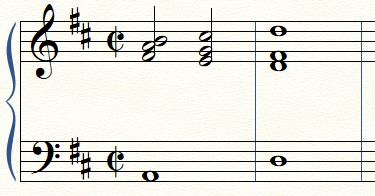

An interval is the distance between two different pitches/notes. The two different notes can either occur at the same time (called a harmonic interval) or consecutively one after another (called a melodic interval).

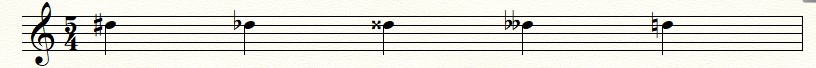

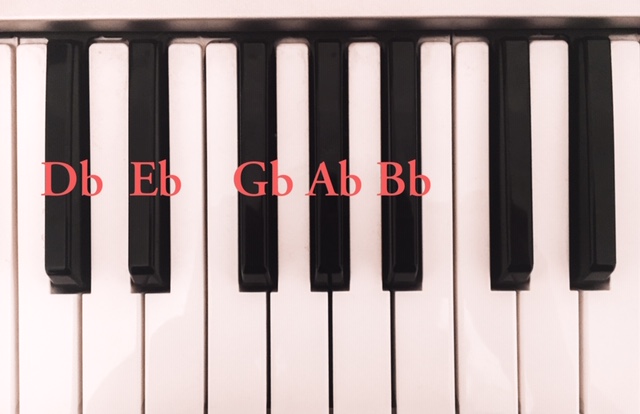

The smallest, and most basic, interval used in Western music is the semitone/half-step. A semitone is the distance traveled from one key on a piano to the next adjacent key. Combining two semitones together make a whole-step. Half- and whole-steps make up a lot of the fundamentals understanding different aspects of music.

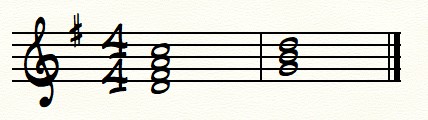

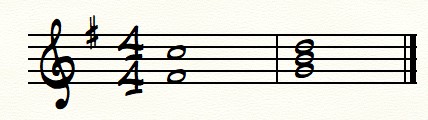

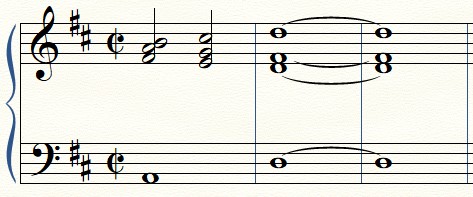

Now, what do we call intervals that aren’t two notes right next to each other? Below is a graph that I’ll explain:

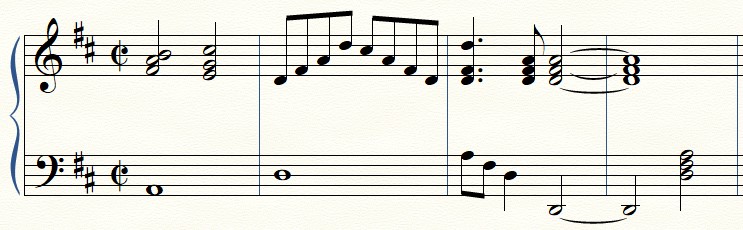

The first process of finding the name of any interval is counting how many semitones it is made of. Start with the lowest note of the pair and count on the keyboard how many semitones are traveled to reach the higher pitch. From there, look at the letter names. How far apart are they? Remember: the letter names go in a repeating ascending order of – A B C D E F G A B C D … From there, you can find on the graph above what to name the interval.

So, say you went from middle C to G3. G3 is lower than middle C (otherwise known as: C4), so let’s count up from there. Middle C is five semitones above G3. Counting letter names we get: G A B C , which means a distance of three letter names were traveled. From all this information, we can conclude that this is a perfect fourth of P4 in abbreviation.

Thank you so much for taking the time to read! Feel free to comment, share, and subscribe for more daily tips below! Till next time.