Continuing with the topic of blues, there is an other option – an abridged version – of the 12-bar blues structure. In the progressive development of rock music in the 50’s and 60’s, many artists began writing songs using the commonly available blues chords and harmonic movement… but in a short 8 measure cycle.

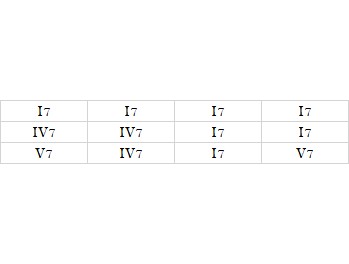

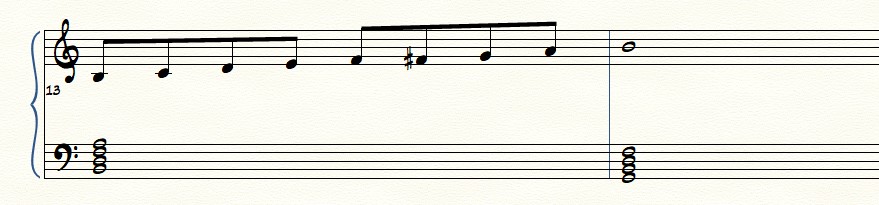

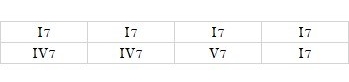

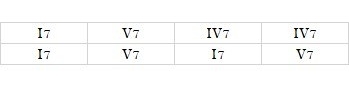

Below are some various harmonic progressions that are commonly found in sounds that are built off of the 8-bar blues structure:

Once again, this is just a beginning frame. You can most certainly experiment with substituting chords and changing other factors. Like how an artists needs a canvas to first structure their genius, so does a composer.

Thank you so much for taking the time to read! Feel free to comment, share, and subscribe for more daily tips below! Till next time.