So you have the chord harmony you want to play, and you have decided which instruments to play it… now what?

Well, here are three things to keep in mind:

- Density

- Weight

- Span

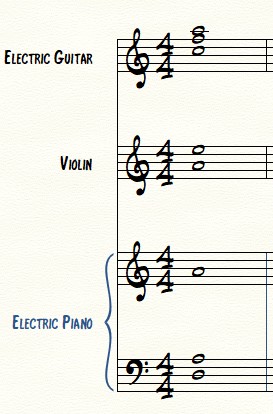

Now, let’s take a look at these three aspects in use with the example below (remember that the guitar is played an octave lower than written):

First, density. That has to deal with how many different pitch classes there are that make the harmony. In the example above, there are 5 different pitch classes {D – F – A – C – E} which form a Dmin9 chord. Relatively, this is more dense than a simple triadic harmony.

Next, weight. What pitch class appears the most? Even though the harmony is structured to be a Dmin9 chord, the A4 pitch is sounded in all three instruments. That means there is less weight on the root of the chord, and more on the 5th.

Finally, span. Span deals with how the dense harmony is spread throughout an octave ore more. From the example above, the range of the harmonic span goes from D3 to E5, which is more than two octaves. So, we can realize that the sound of this will be spacey – and not so condensed.

Keep these in mind as you are consciously thinking about how to voice your chords.

Thank you so much for taking the time to read! Feel free to comment, share, and subscribe for more daily tips below! Till next time.