To remind: when you are in simple meter (4/4) the beat is easily divided into 2s or 4s, and when you are in compound meter (12/8) the beat is divided into 3s or 6s. Review old posts if you are not familiar with these concepts.

However, just because you are in simple meter doesn’t mean that you can’t incorporate compound meter divisions.

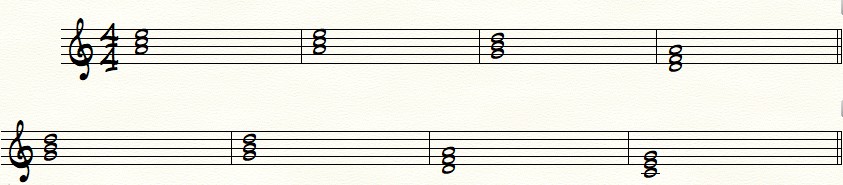

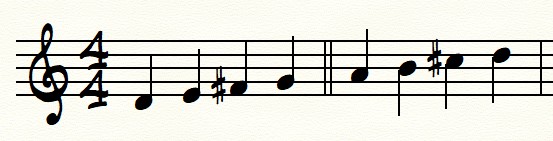

Take an example below:

We know that this piece is in duple meter because the time signature is 4/4, but there is a figure notated with a “3.” This is called a triplet, and it appears in duple meter pieces to tell the performer to divide the beat into three eighth notes of even length instead of two – just as you would find in a compound meter.

This can happen in reverse, too…

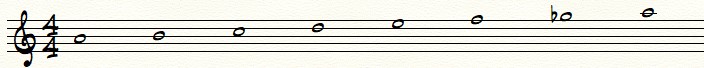

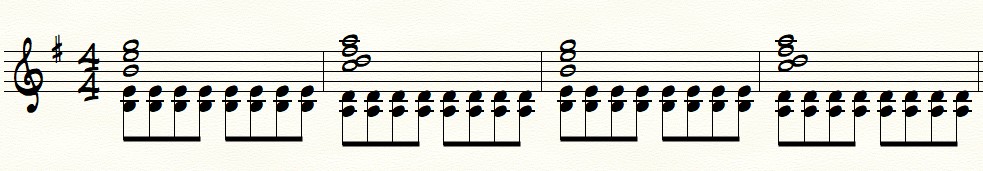

Thae a look now at this example:

This piece is in compound meter (12/8 and the beat is divided into 3s), but there are two figures – one noted with a “2” and the other with a “4.” They are called duplets and quadruplets respectively, and they divide the beats in compound meter pieces into even divisions.

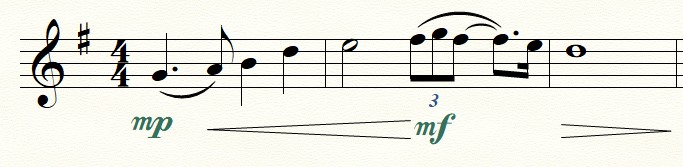

Practice performing switching between these different divisions.

Thank you so much for taking the time to read! Feel free to comment, share, and subscribe for more daily tips below! Till next time.