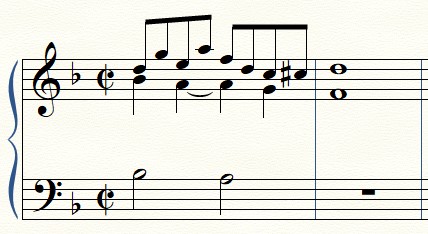

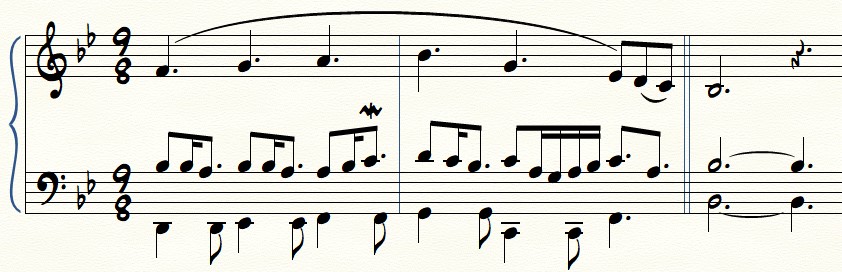

In a previous tip post, we talked about the idea of the call & response. Say, for example, you have a harmonic progression with set-in-stone musical themes that will act as a “call,” but are missing the “responses” in between:

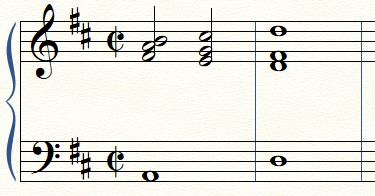

Four ingredients to a tasteful execution of a response are: 1) space, 2) pitch, 3) rhythm, and 4) judgment.

For space, decide if the response need to occur immediately after the termination of the call, or if there can be measures of rest in between.

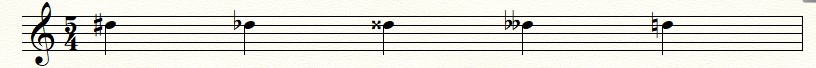

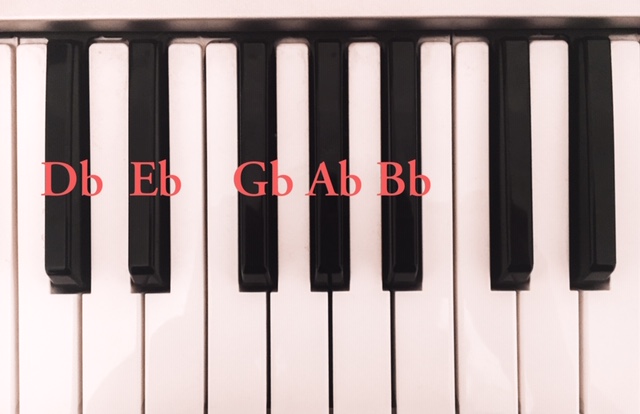

Aim to land on chord tones on strong beats, but don’t be afraid to add passing and chromatic pitches!

A good flow of rhythm would be to start as an anticipation on a weak part of the measure entering a stronger beat. Ending on a strong beat, too, can sound good – but that is up to the composer.

And finally, have good taste/use of economy as to what is needed and best complements he figures.

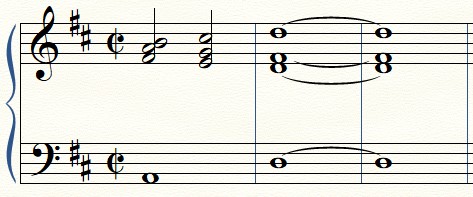

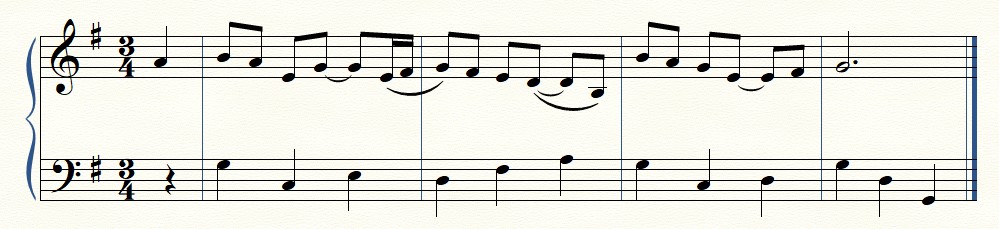

Here is a rough draft of adding “fills” to these previous blank measures:

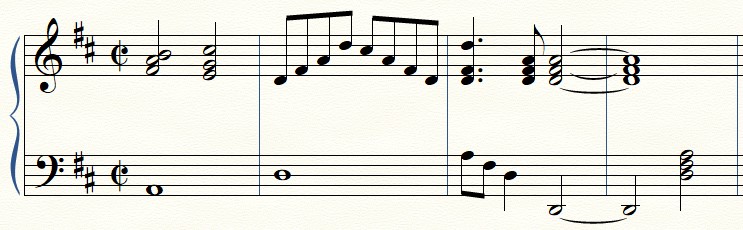

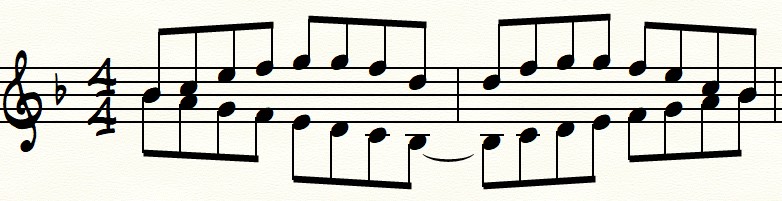

In this case, space is tight – which means constant flow. Also, the response has its own unique shape while staying within the chordal tones. These are some nice qualities. However, there are breaks of silence between that can be abrupt. So, by incorporating an anticipating figure, and modifying the rhythm to look similar to the call, the response is workshopped into something completely better than before:

Thank you so much for taking the time to read! Feel free to comment, share, and subscribe for more daily tips below! Till next time.