Being in the music industry, I find too often people trying to make a living by selling “beats,” implying that the word is synonymous to their cool groove they spent hours on with their laptop program for upcoming rap artists that are so fire. Let’s make this clear…

A beat is the pulse in a piece of music. That’s it. When you are listening to your favorite song, you are more than likely tapping your foot or nodding your head in-time to the beat. Of course, you might be hearing some notes that appear on the beat – or within the beat. In the grand hierarchy scheme of things, the notes that appear between the main pulse are part of the beat divisions or subdivisions.

But now we need a framework; so we incorporate meter, which is how beats are divided and grouped into larger recurring units giving emphasis to certain beats. You have already seen this in place on a score with the use of measures grouping notes together and having the bar lines on the staff separate the measures from one another.

The first beat of a measure is called a downbeat and gets the most power. On the opposite end of the spectrum, we have the upbeat which is the lightest and appears before the downbeat on the last beat of the previous measure. So just before the bar line.

So the first way to categorize meter is by how the primary beat is divided. If the beat is easily divided in two, then it is a simple meter. On the other hand, if the beat is divided into three, then it is called a compound meter.

Groups of two or groups of three essentially. Now, the next way to categorize is by how many groups there are. If there are two groups of two/three, then it is called duple meter. Three groups mean it is triple meter, and four groups is quadruple meter. So, if we have three groups of beats that are easily divided into two, we should call it: simple triple meter.

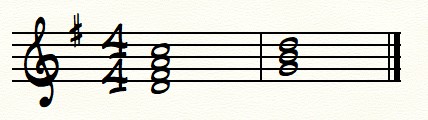

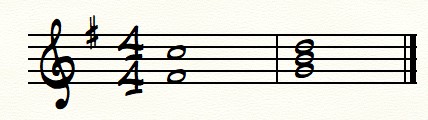

In the examples shown, you’ve probably seen two numbers that somewhat look like a fraction found in math. These “fractions” are your meter/time signatures that tell you the meter type. The top number tells how many primary pulses are within a measure, and the bottom tells the beat unit — more on that to come next time!

Thank you so much for taking the time to read! Feel free to comment, share, and subscribe for more daily tips below! Till next time.