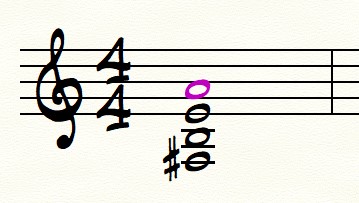

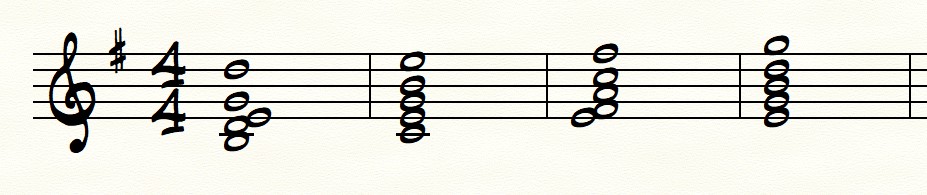

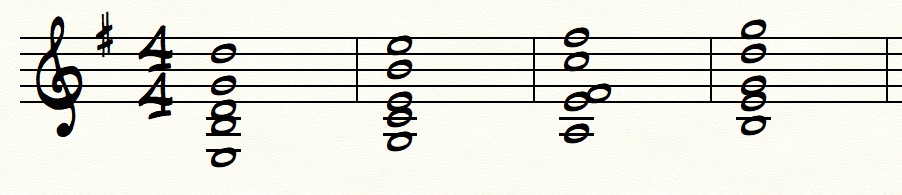

One interesting idea that I just read about that I want to share with you all is on how to orchestrate the closed fifth cluster.

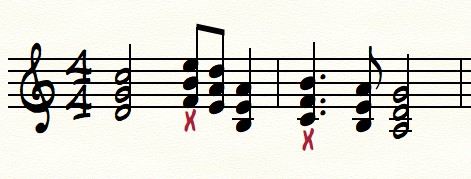

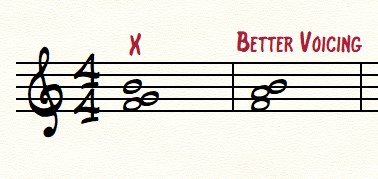

To remind, the structure of the closed fifth cluster is a major or minor triad in root position with an extra note added a perfect fourth below the melody note.

The orchestration revolves around the idea of separating between two orchestral families.

In other words, try having the three notes that form the major/minor triad from one instrumental family in your orchestration while having the extra tone of the cluster come from a completely different instrument.

Not only will this create a variety and blend in the timbre, but it will also make the “cluster” sound become more pronounced.

Thank you so much for taking the time to read! Feel free to comment, share, and subscribe for more daily tips below! Till next time.