What is Kwela music?

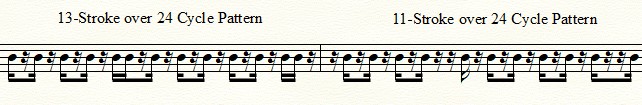

It is pennywhistle-based folk music played in the streets of South Africa, playing decorated jazzy/blues-y melodic lines over a cyclical harmonic progression.

The name, “Kwela” has nothing to do with any music aspect. In fact, it is a verb from the Isizulu and African Bantu languages meaning “to climb.” Prior to this become an established music genre, it was used as jargon and also as code among kids to warn when the police was coming by. If they couldn’t hide, they would act innocent by taking out their pennywhistles and playing this lively skiffle music.

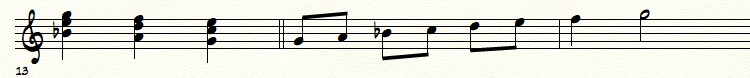

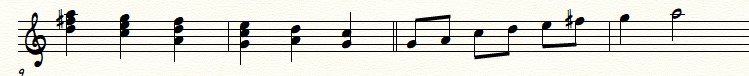

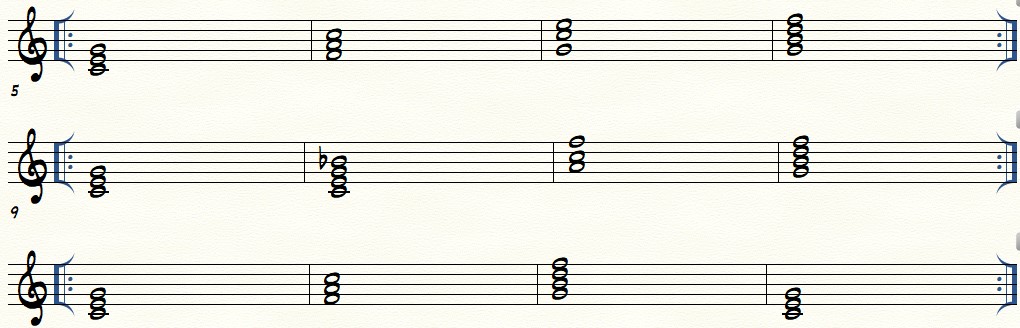

While the melody was improvised using select pitches from the blues scale, the harmonic progression was always a recurring variation of one of these three:

Play around with these chord progressions by having yourself record or use a DAW to playback as you improves a melody line over it.

Historically, these progressions then influenced the blues because so many South Africans had their ears tuned to the Kwela music harmonic predictability. Thus, the common 12-bar blues were adapted into these variations:

Once again, play around with these progressions to feel where and how the harmonic forces are different from the “original.”

Thank you so much for taking the time to read! Feel free to comment, share, and subscribe for more daily tips below! Till next time.