In some south and central African countries, musicians use homophonic multipart singing style in their songs. That means that the group of people sing the same song rhythmically, but move in parallel motion at different pitches. Typically, it is a fourth (interval) apart, but not always.

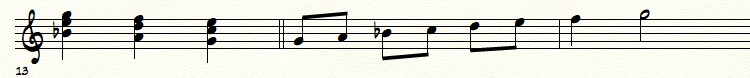

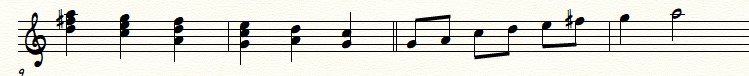

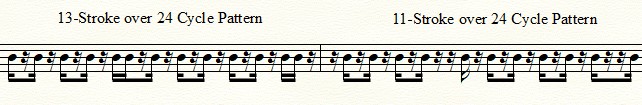

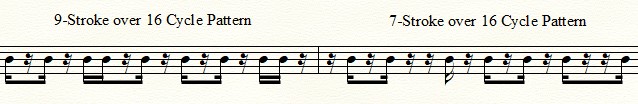

Below is an example of a multi-part harmonic progression called the MpyƐmɔ tribe progression from the Central African Republic as well as the derived scale. Notice how skipping every other note in the scale on the right produces the functional harmony on the left. Also, observe the pitch fundamentals that build the harmony as well as act as a bourdon (open drone).

Besides advising you, the reader, to experiment, investigate, and take inspiration from these African harmonic progressions I strictly indorse you not to impose classical theory on these progressions. While it is tempting to analyze these progressions with the idioms of Western music notation, I recommend not to as it takes away the purity/authenticity of African music’s own stylistic practices by framing it within a box.

Thank you so much for taking the time to read! Feel free to comment, share, and subscribe for more daily tips below! Till next time.